The Impact of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict on the Dynamics of Russians’ Material Well-being

Vladimir Zvonovsky

Mar 31, 2025

Executive Summary

The Russian economy, in the conditions that arose after the start of the special operation and then mobilization, has been hit by several shocks. Yet from the point of view of most ordinary Russians, the economy seems quite stable, which is reflected in adaptation to the new reality by the main social groups.

Normal, peacetime economic growth entails people’s financial well-being improving when they create new products and promote economic efficiency and development. Yet with the rise of the wartime economy in Russia, it is those able to take advantage of the lavish fiscal spending who have adapted more successfully to the new political and economic reality.

We have identified three phases of adaptation of various groups to the new reality. In the first phase, from the time the special military operation started until approximately mobilization in autumn 2022, young people, residents of Moscow and St Petersburg, private-sector workers and people with higher education were most likely to say they had taken a hit financially. Meanwhile, state employees, pensioners, older Russians and residents of small towns felt better. In the second phase, from the start of mobilization in autumn 2022 until approximately autumn 2023, Russian business began to adapt to the new reality, and private-sector employees and businesspeople began to assess their financial situation similarly to state employees and pensioners. In this phase, thanks to lavish fiscal flows, residents of regions bordering Ukraine grew more upbeat about their financial situation than residents of Moscow and St Petersburg and of Russian regions located far from the fighting. In the third phase – approximately the second half of 2023 – an economic system crystallized in which regions and social groups that had been “left out” before the conflict (e.g., older people, people without higher education) thought their chances of getting a bigger slice of the economic pie had gone up. But the economic boost felt by these “periphery” social groups turned out to be very short.

It is hard to say exactly when the third phase ended. But today the economic structure of Russian society has gone back to how it was before February 2022, and expectations that new heroes and social groups would gain the upper hand thanks to the Ukraine conflict have proven unjustified. Traditionally privileged groups have adapted and retained their advantages, while worse-off supporters of the intervention, who had hoped for a redistribution of wealth that would benefit them and boost their social status, have been disappointed.

The stability of an economic system is judged by the stability of the rules and means available for achieving financial success, hence the loss of economic stability means changed rules and means, elevating some and lowering others: the lot of the groups that are better positioned to benefit from the new rules and means improves, while the prosperity of the other groups that do not fit into the new order rapidly declines. Since February 2022, various social groups have tried their best to adapt to, and take advantage of, the new economic reality taking shape.

To gauge their adaptation, throughout the conflict our colleagues have asked Russians: “in your view, has your financial situation improved, worsened or basically stayed the same in the last 2-3 months?” This approach is widely used in both Russian and international research.

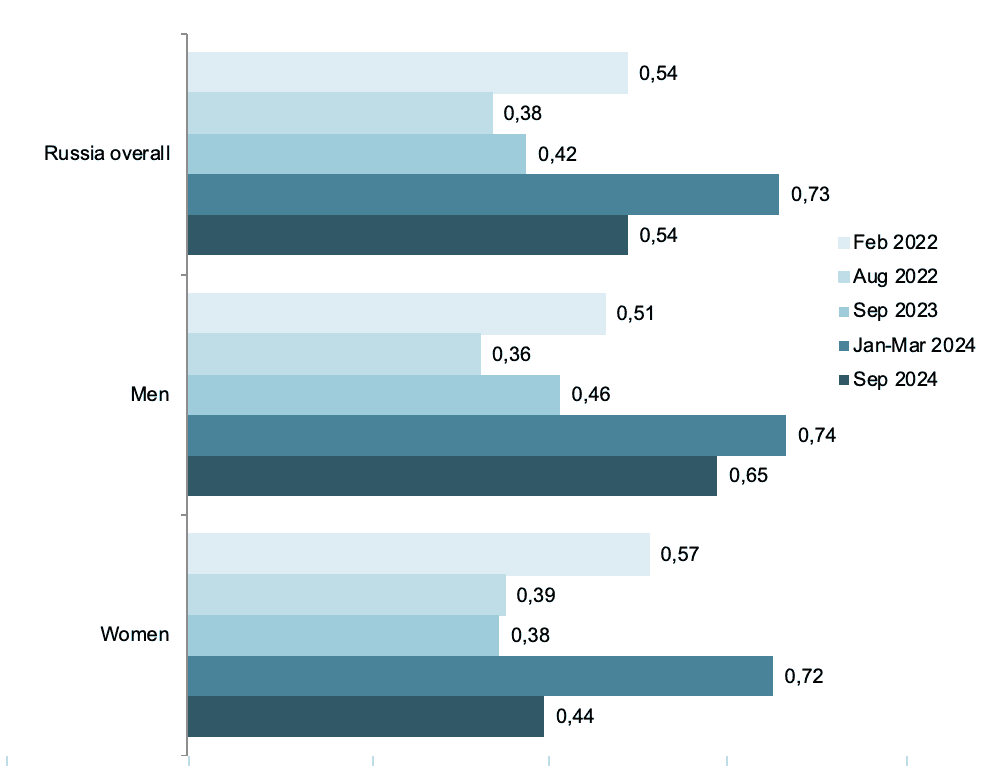

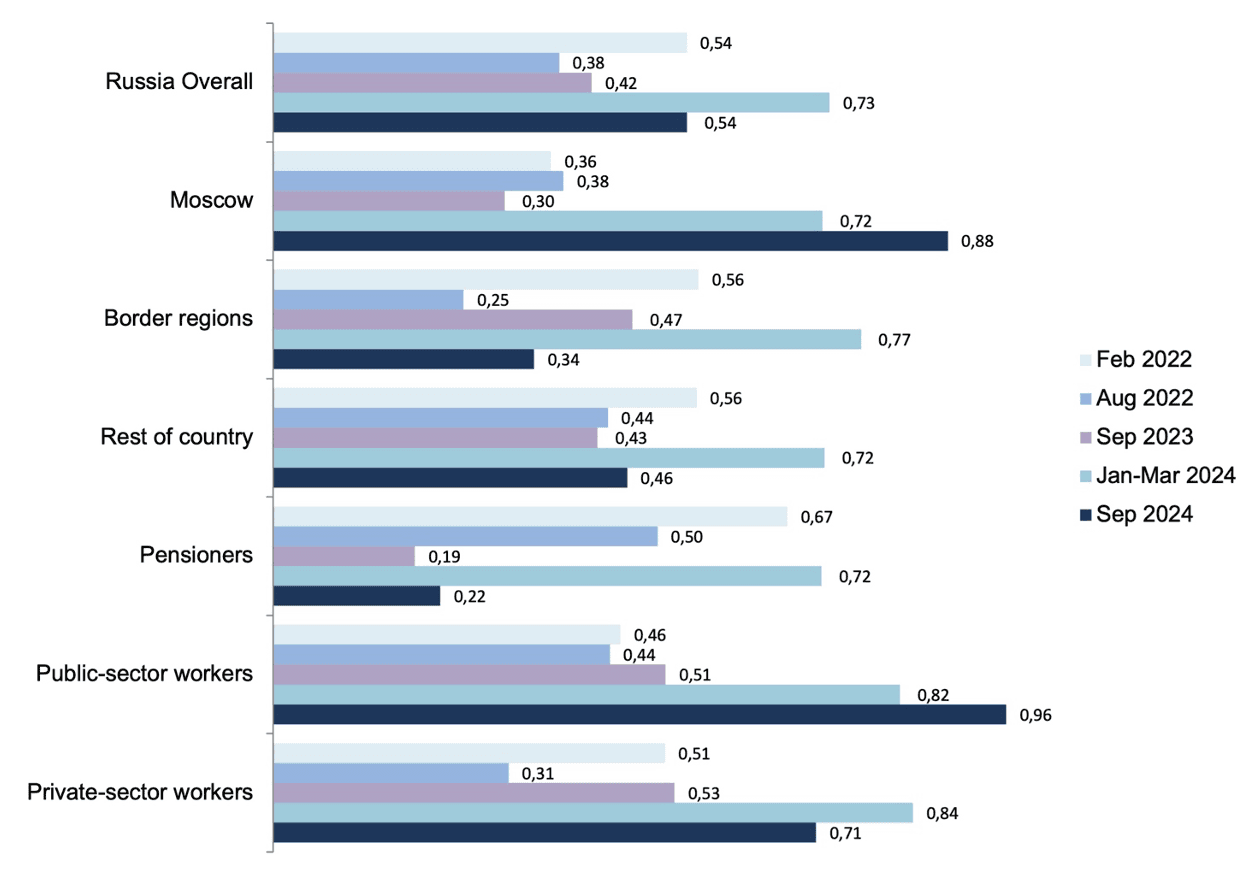

Dynamics of the backward-looking prosperity index

The ratio of the share of people whose financial situation improved over the last year versus the share of those whose situation worsened is measured using what we call a “backward-looking personal prosperity index” to arrive at an integrated assessment of changes in prosperity.1 If the value of the index is equal to one, this indicates equal positive and negative assessments of changes; an index value less than one indicates a predominance of negative assessments; and a value greater than one indicates a predominance of positive ones. As seen in Table 1, the average for the country in September 2024 came in at 0.54, whereas at the beginning of the year it was 0.74, matching multiyear highs.2

Table 1. Perceived changes in Russians’ financial situation from February 2022 to September 20243

;Feb 2022; Aug 2022; Sep 2023; Jan-Mar 2024; Sep 2024 Index; 0.54; 0.38; 0.42; 0.73; 0.54

Improved; 17%; 13%; 14%; 17%; 15%

No change; 49%; 53%; 53%; 60%; 58%

Worsened; 31%; 35%; 33%; 23%; 27%

This is confirmed by data from pollsters. The Levada Center has found that Russians gave the most positive assessments of their financial situation in the last 15 years at the end 2023/beginning of 2024. In addition, immediately after the start of the intervention in Ukraine, the proportion of Russians who said their financial situation had worsened in the last year dropped off. A similar trend can be seen in data from the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM), which asks Russians about changes in the last 2-3 months.

By the end of 2022, Russians had grown less sanguine about their financial situation. This was due to the exit of many Western companies from Russia, combined with the closure or relocation of Russian businesses and major logistical issues. But starting around the end of 2023, when the model of the wartime economy had crystallized, large swaths of the population said their financial situation had improved.4 This likely peaked in the first half of 2024, and the problems inherent in that model, hitherto tolerated, increasingly became a burden.

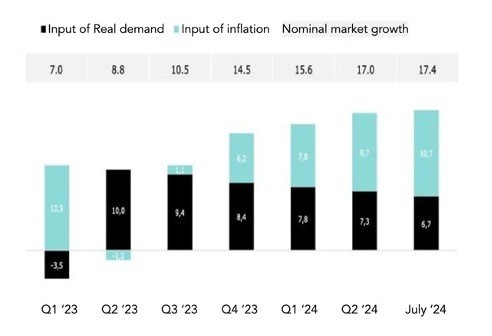

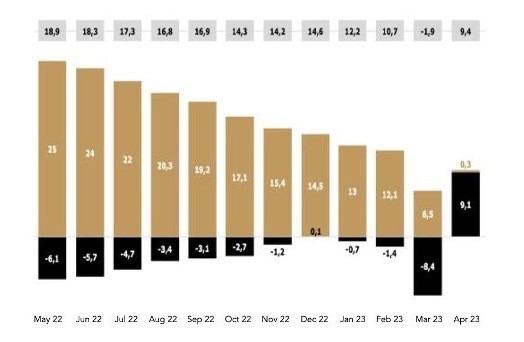

These trends in how people see their financial situation are supported by hard data on retail sales. According to NielsenIQ (monitoring of retail chains conducted by Scantrek), a gradual slowdown in inflation in 2022 was accompanied by a decrease in Russians' consumption. In the following year, retail sales began to grow from the second quarter, but with each subsequent period, the contribution of inflation to this growth was higher and higher, and real growth was less and less. Inflation probably was on the rise through the end of 2024, and sales will decrease. Thus, retail sales seem to back up Russians' subjective assessments: the period of income growth, optimism and heightened consumer activity in 2023 was replaced by one of high inflation and increasing pessimism. Figure 1 & 2. Dynamics of retail sales volume in Russia, adjusted for inflation. Source: Nielsen IQ

More important than the change in trends itself is where it has been playing out, i.e., among which social groups. To assess that, we will break down the broad dynamics laid out above.

At the beginning of the conflict, men and women assessed their economic fortunes approximately the same, but in 2024 their assessments began to diverge. In early 2024, the share of “no change” responses among women was significantly higher than among men, indicating that men were more polarized about their ability to economically win or lose in the context of the special operation. By the year-end, the share of men who said their financial situation had improved increased more than that of women. The new conditions likely create a more dynamic, polarized environment for men than for women.

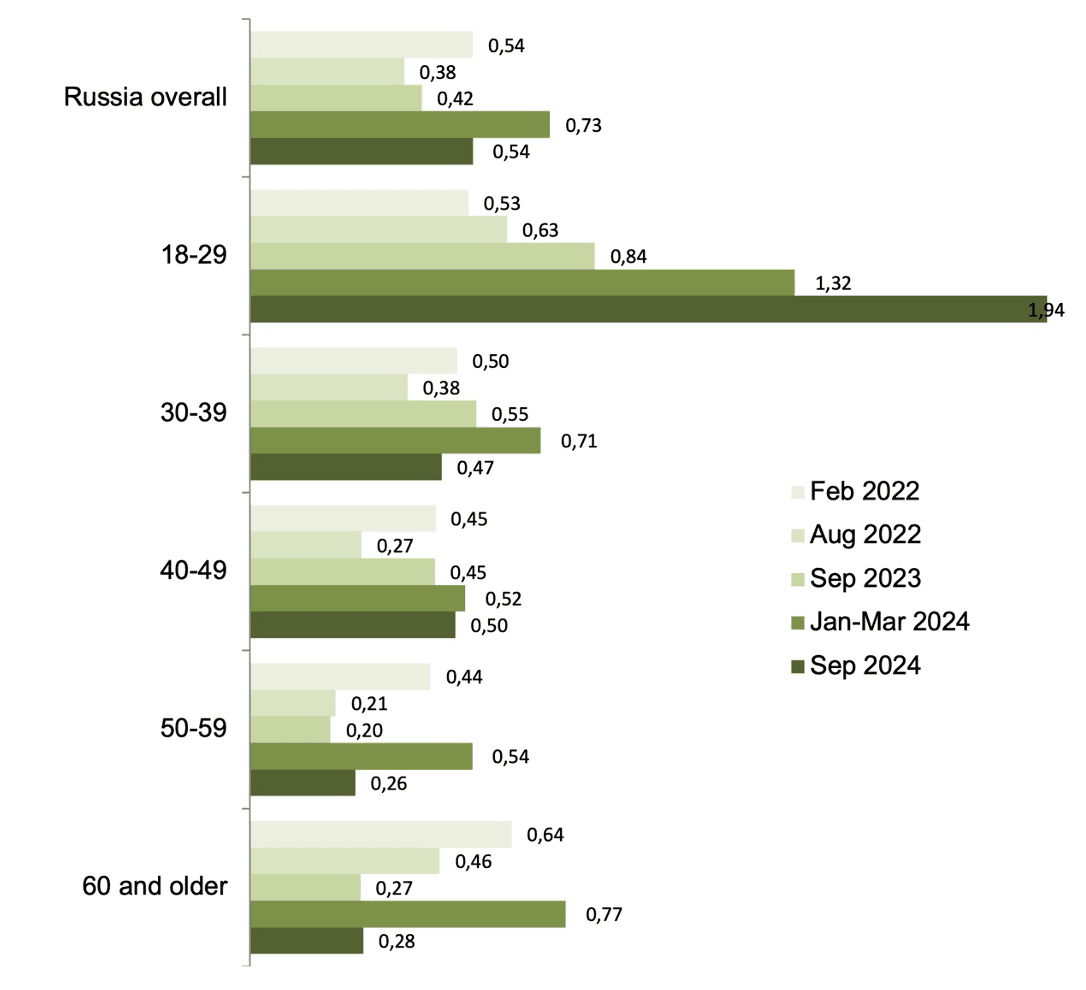

Figure 3. Dynamics of the Material Well-Being Index by Gender, 2022-24. Source: Chronicles, ExtremeScan

Differences across age groups have deepened, as well. Younger generations assess their financial situation more positively than older generations, i.e., Russians entering the labor market for the first time feel are rather confident about their economic prospects. Whereas the difference in the index values between the youngest and oldest age groups was 0.57 in September 2023 and 0.56 in January-March 2024, it had expanded to a whopping 1.49 by September 2024. This is further evidence that the previous economic model has returned, with older people leaving the labor market not feeling the benefits of economic growth.

Figure 4. Dynamics of the Material Well-being Index across Different Age Groups, 2022-24.

Source: Chronicles, ExtremeScan

Overall, amid the headline growth of the Russian economy, the most optimistic groups are those that can compensate for economic problems, primarily inflation, by demanding higher wages either at their current place of work or by changing it, with the labor shortage in Russia playing into their hands. Groups that do not have such opportunities not only feel less optimistic or pessimistic, but the gap between the economically “successful” and “unsuccessful” seems to be growing.

Figure 5. Backward-looking personal prosperity index across selected groups in Russia, 2022-24.

Source: Chronicles, ExtremeScan

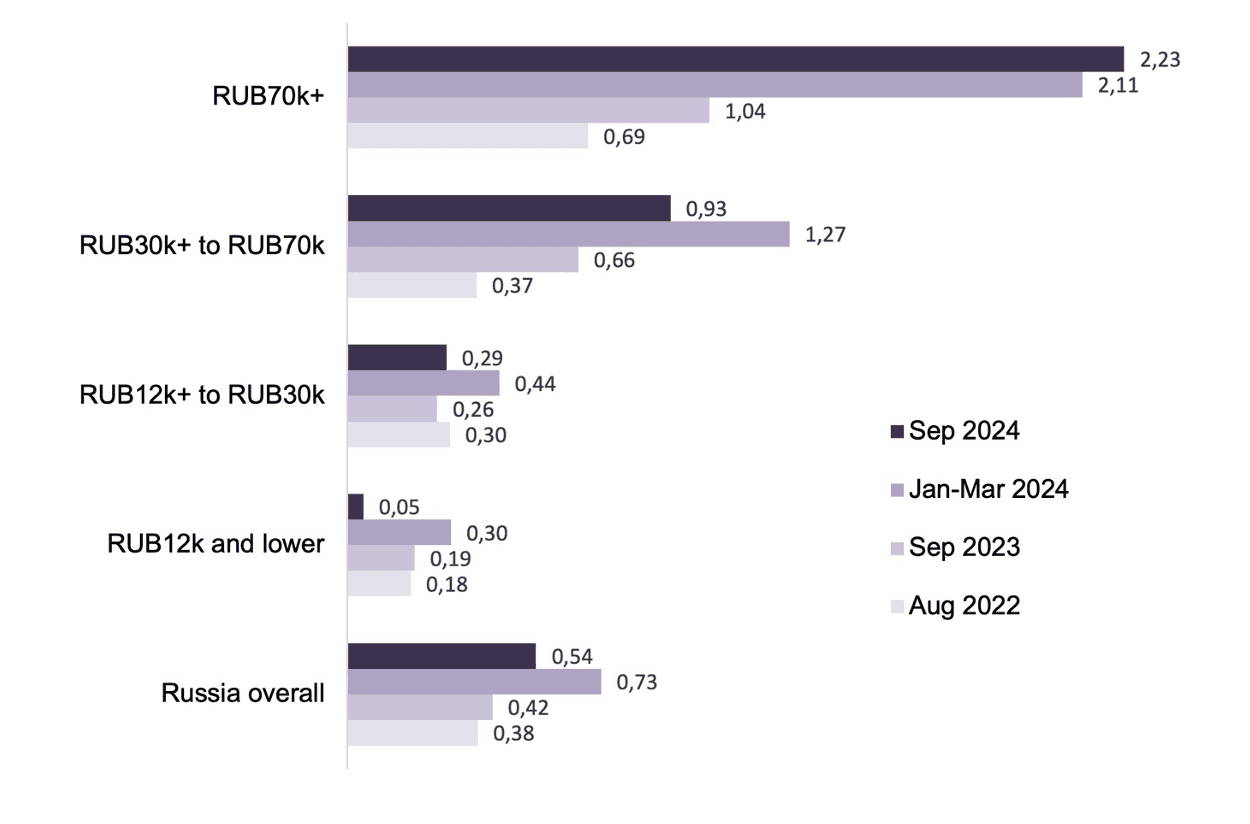

In the first months of the wartime economy and life under sanctions, high-income groups were hit hard. Economists have noted this, pointing out that a wobbling Russian banking system actually confiscated some foreign-currency deposits of Russians, who most likely belonged to these groups.5 After mobilization in autumn 2022 and the engagement of wider groups of the population in the conflict – both as soldiers and as workers fulfilling state defense orders, through “parallel imports,” etc. – the state boosted wages significantly.. As a result, these groups began to feel less deprived of income (though the overall balance of assessments remains negative) than a year ago and than social groups outside the current labor market.

The higher one’s income, the less likely one is to say his/her financial situation had deteriorated, and such patterns became more pronounced from early 2024. The exception was the highest income group. As 2024 progressed, the index values for all other income groups significantly declined from their wartime peaks reached in January-March 2024, while that for the top group kept increasing to peak in September 2024. Summarizing, we can say: different income groups previously felt that their lot was getting better and better, now it is only the highest earners. Adaptation to the new reality has been derailed for all but them. Figure 6. Backward-looking personal prosperity index across various income groups, 2022-24.

Source: Chronicles, ExtremeScan

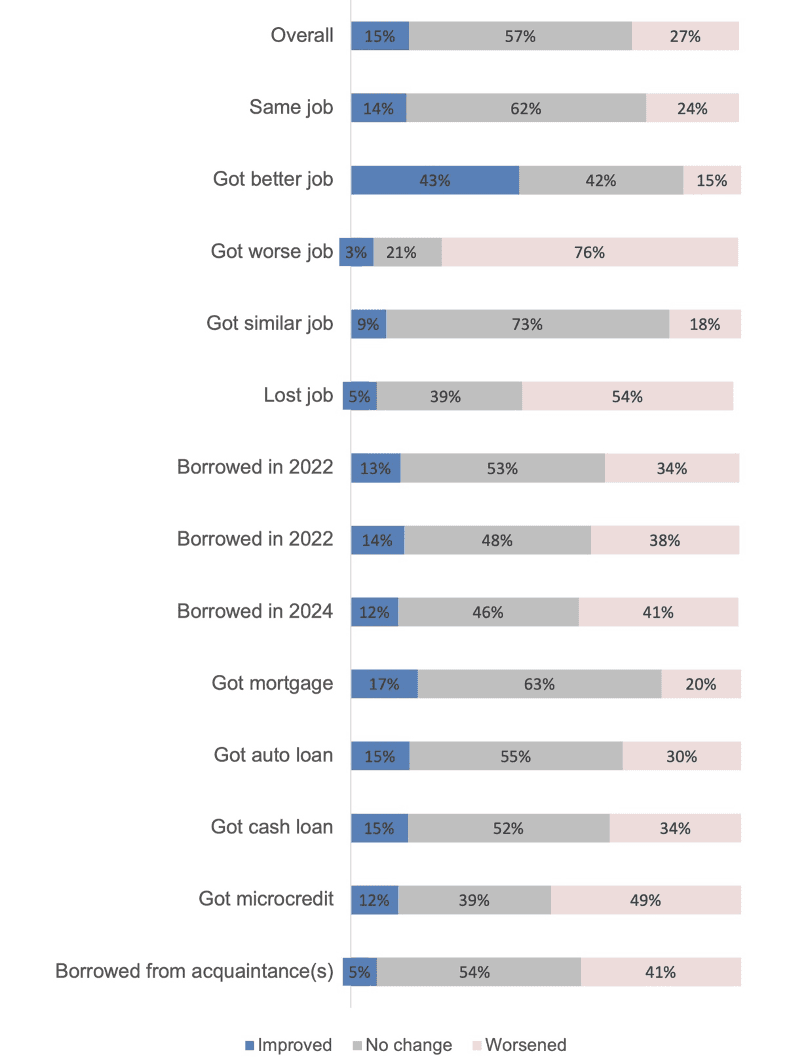

People take out loans for different reasons. Some do not have enough money until their next paycheck, while others have enough and decide to borrow more to buy a car, household appliances or even an apartment. In Russia, borrowing from a lender most often suggests a deterioration in the borrower’s financial situation. Among respondents who took out a loan, the share whose financial situation rhetorically worsened in the last year was 34% in 2022, 38% in 2023 and 41% in 2024. Still, the share of those who took out a loan has declined.

Figure 7. Adaptation to changing reality among groups with different economic circumstances.

Source: Chronicles

These dynamics correlate even more strongly with the stated purpose of the loan. A mortgage or car loan does not allow for conclusions to be made about the borrower’s financial situation. But a sign that a borrower is facing financial difficulties is the history of a cash loan to buy consumer goods or a loan from a microcredit organization (34%), as is borrowing money from friends and relatives (49%).

Yet people’s job has a much bigger impact on how they assess their financial situation. Among those who found in the last year a new job where they are paid better, 43% say they are now better off financially (43%). Compare that to those who lost their job or switched to a worse paying job, who are much more likely to say they are now worse off financially (54% and 76%, respectively). The impact of people’s job on their assessment of their financial situation likely reflects a certain combination of pay, employment terms and the nature of the work.

The success of one’s adaptation to the changing reality is driven chiefly by the source and size of one’s income (i.e., his/her job), access to loans and consumption behavior. The better the job, the more access to money and the higher the consumption opportunities, the higher people tend to assess their personal financial situation.

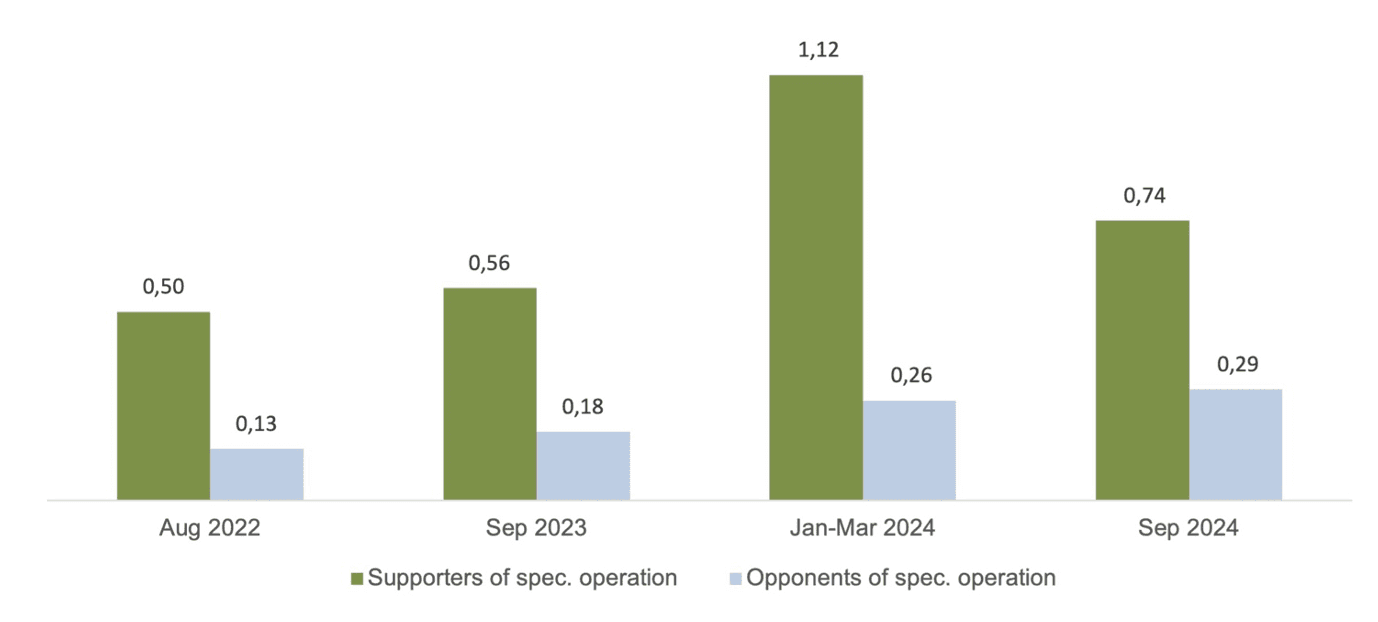

Noneconomic factors are also at play. Qualitative research shows that disapproval of key political events darkens perceptions of their consequences. Opponents of the military intervention in Ukraine tend to focus more on accompanying economic problems and undersell their own financial situation, while supporters, on the contrary, are less moved by those economic problems since they are associated with political decisions that they support.6

Therefore, the latter group assesses changes in their own financial situation more positively than the former group. Moreover, as can be seen in Figure 8, at the beginning of the third year of the conflict, the share of supporters of the intervention in Ukraine who reported an improvement in their financial situation was higher than the share who reported a deterioration (1.12 index value). But after six months, the figure had again fallen below one, to 0.74.

Meanwhile, among opponents of the special military operation, the backward-looking personal prosperity index has risen since 2022 (from 0.13 to 0.29), indicating their gradual adaptation to the new reality. Intervention supporters are more driven by current events, with their assessments more fluid. As Russians’ perception of their standard of living has stabilized over the course of the conflict, their assessments have grown more “political” and less “economic.” Opponents of the special operation continue to understate their financial situation, while for supporters it depends on the situation on the battlefield. Figure 8. Backward-looking personal prosperity index among supporters and opponents of Ukraine intervention, 2022-24. Source: Chronicles

Three phases of adaptation to wartime conditions

We have identified three complete phases of how Russians have adapted to the new reality and changing economic conditions .7 In the first phase, from the time the special military operation started until approximately mobilization in autumn 2022, young people, residents of Moscow and St Petersburg, private-sector workers and people with higher education were most likely to say they had taken a hit financially. Meanwhile, state employees, pensioners, older Russians and residents of small towns felt better. Thus, economic the prewar “winners” and “losers” had switched places.

In the second phase, from the beginning of mobilization in autumn 2022 until approximately autumn 2023, Russian business began to adapt to the new reality, and private-sector employees and businesspeople – particularly those producing things for the special military operation and those helping to get around foreign sanctions to import goods into Russia – began to assess their financial situation similarly to state employees and pensioners. It was also during this time that huge fiscal inflows into border regions boosted assessments by residents of these regions above those by residents of St Petersburg and Moscow and regions farther from the front line. In addition, some Russians who had previously strategically built their businesses in the West returned to Russia, citing sanctions headwinds and the broad confrontation between Russia and the West.8

In the third phase – approximately the second half of 2023 – an economic system crystallized in which regions and social groups that had been “left out” before the conflict (e.g., older people, people without higher education) thought their chances of getting a bigger slice of the economic pie had gone up.9 Already by early 2024, the peak of people’s assessments of their financial situation had passed, however. By then, young people seem to have felt well-adapted to the new reality, which signaled a return to the prewar state of affairs, where the most positive assessments came from young people, residents of Moscow and St Petersburg, private-sector workers and high-income groups of the population. Major geographical differences disappeared in the third phase: Muscovites looked at their economic fortunes about the same as residents of Russia’s provinces, be they close to the front line or not. The economic boost felt by “periphery” social groups turned out to be very short.

In winter and spring 2022, many Russians who generally supported the military intervention in Ukraine hoped that the conflict, together with the break in economic and political relations with Western countries, heralded a return to state paternalism. Expecting that such a shift in economic policy would improve their own lot, they loyally supported the government’s special military operation. But these hopes proved forlorn, and disillusionment with the new reality has grown:

On the one hand, they [the government] mobilized society, and society became more unified. We were ready to do as they told us… When the war began in 2022, the special military operation, everyone believed that now everything in the country would really change and the people would be different. And the country was mobilized. Everyone was ready. And finally, all these traitors and vile people had gone off to the West, and the most active, the most energetic, the most proper, the most noble and the most intelligent people, the most decent people, remained here. There would be order in the country... But what we got is the grandma in the Donbas coming out with a red flag… Everything has stayed the same, like with the grandma. No nationalization… And despite everything is even worse.(Male, 54 years old, 2023)10

It is hard to say exactly when the third phase ended. As with the other phases, there is no specific event or opinion poll that clearly separates one from another. The fact is, however, that over the course of last year, the third phase gradually gave way to the fourth, with the most financially sure groups from before the special military operation regaining their confidence – young people, residents of Moscow and large cities, high earners and big consumers. Meanwhile, the least financially confident were again residents of small towns, older generations, pensioners, low earners and people living from paycheck to paycheck, and people with modest consumption habits.

In other words, the same groups remain at the top and bottom of Russia’s social hierarchy as they did before the war. Hopes that the “cleansing” effect of war would elevate new heroes and groups to reshape Russia’s future have proven futile. Traditionally privileged groups have adapted, preserving their advantages and stymying social mobility, while economically and socially disadvantaged supporters of the intervention in Ukraine – who had envisioned a redistribution of wealth and status in their favor – have seen their expectations go unmet. So far, this frustration has not significantly influenced their assessments of the economy or (especially) politics. But if these already-disillusioned groups grow more despondent, their support for the intervention in Ukraine as a means of transforming Russian society could wane. Even so, one should not underestimate the power of Russian state propaganda, which remains highly effective in shaping perceptions and deflecting dissatisfaction toward “external and internal enemies.”