“Preserving a Language Involves Everything that Makes a Language Popular…It’s not Something that Lies in Your Grandmother’s Old Trunk and Only Comes out at Festivals”

Dmitry Oparin and Vlada Baranova

Aug 14, 2023

This interview is part of a collaborative project between the Russia Program and Perito, an online media platform on culture and territories. Through a series of translated interviews and essays, we introduce Perito's content on Russia and Russia's minorities to English-speaking audiences.

There are many different field researchers working in Russia — anthropologists, ethnographers, sociologists, sociolinguists and others. Perito, along with anthropologist Dmitry Oparin, is publishing a new series of articles where they will regularly talk with different specialists about how their work is changing. Each interview is a story about a facet of Russian life today.

The first article is devoted to language. Dmitry Oparin spoke with sociolinguist Vlada Baranova (Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies) about the politicization of language activism and the importance of linguistic democratization, and whether the Russian state really poses a danger to minority languages.

Dmitry Oparin: Please tell us about your scientific career. What do you do as a researcher? What subjects excite you?

Vlada Baranova: There are two main fields in my life that are important to me both emotionally and academically. The first is Mariupol a city in eastern Ukraine that was heavily damaged during the Russian invasion and is home to a large Greek community. Two groups of Greeks live there: one is Turkic-speaking, they call themselves Urums, and the second is the Rumeans. I went there for the first time when I was still getting my bachelor’s. In 2010, I published the book Language and Ethnic Identity. The Urums and Rumeans of the Azov Area about how language and ethnic identity are connected, and how these multilingual groups perceive themselves.

A little later, I wanted to change my subject of study and research field for a while, and I was invited on an expedition in Kalmykia to learn Kalmyk. For the past five years, I’ve been studying Chuvash and traveling to Chuvashia, in the Poshkart Region. In tandem, I was working on the sociolinguistics of migration in Saint Petersburg — I studied how a multilingual city works, how newcomers learn or do not learn Russian, how they use or do not use their native languages. I was interested in how multilingualism works visually. We had great projects with an interactive map of multilingual signs and announcements that people created by sending photos through the LinguaSnapp SPb mobile app.

Now you’re primarily engaged in studying Kalmyk. What place does it occupy on the map of Russian languages?

Kalmyk, to my great regret, is not yet counted among the most well-preserved minority languages in Russia, unlike Tuvan, Yakut and Tatar. This is partly due to the history of deportation and the subsequent hardships the community faced. But the Kalmyks have their own federal subject, the Republic of Kalmykia, and they are a relatively numerous people. At the same time, the actual preservation of the language is at a much lower level than that of many other languages with their own republics, even Chuvash, Udmurt and Mari.

Isn’t there a correlation between the wealth of the region and the level of preservation of the native language after which it is named? Tatarstan and the Republic of Sakha have the funds, while Kalmykia is one of the poorest regions, with residents constantly leaving.

I’m not sure if it’s that straightforward. Tuva is one example of a relatively poor region, and in Buryatia the level of language preservation is still higher than in Kalmykia. In the republic of Ingushetia, in the North Caucasus, the language is highly preserved and their economic position is not particularly favorable.

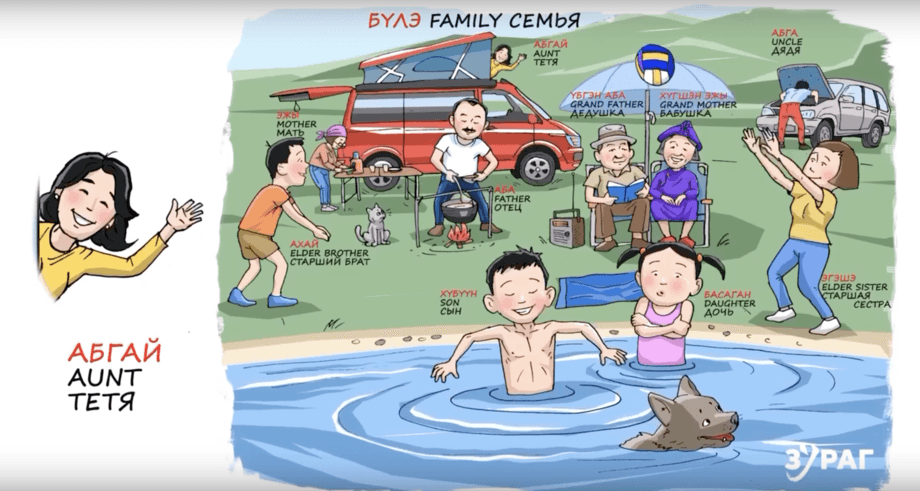

Of course, the wealth of a region affects its ability to invest in its native language policy. There are a lot of programs in Tatarstan that are supported by the republican government, from summer camps for Tatar-speaking children to television broadcasts, podcasts and cartoons. It’s obvious that the poorer the region, the less opportunities they have. Of course, migration also affects the situation. But this is not the only factor.

You say that the condition of the Kalmyk language was affected by the deportation of Kalmyks and other disasters. What disasters are we talking about?

The current bad economic situation and high outflow of people from Kalmykia can certainly be considered one of them. And another thing — I wouldn’t even call it a disaster, but the reaction after the deportations was a desire to be even more Russian than the Russians themselves. Higher education is also highly valued. Everyone wants their children to get a higher education, so they study and teach children to speak Russian very well. Being a competent Russian speaker is prestigious.

It would seem that valuing higher education could only be a positive thing. What could be better for the region’s development? On the other hand, there’s some trauma behind this decision, and an attempt to be a loyal group within the Soviet imperial project. The people were willing to sacrifice the Kalmyk language to travel this path.

Another feature of Kalmykia is very strict, repressive control. The government control has always been stricter in the ethnic regions than in St. Petersburg or Moscow. Because of this, they shut down the lively youth dance parties, where people gathered and danced together in the central square of Elista to the dombra, to native melodies. Participation required minimal knowledge of the language, at least basic greetings. But on the whole, it simply entailed the symbolic presence of Kalmyk youth, representing their Kalmyk-ness on Elista Street. Unfortunately, the organizer was forced to leave, and these events stopped being held.

What language initiatives exist in Kalmykia?

They are varied and extremely good. Awareness that the language is being lost has become a very important issue for the younger generation of Kalmyks. I, for one, am a big fan of this culinary blog, where the creator Bairt cooks and explains what he’s doing in Kalmyk.

There’s a famous stand-up comic in Kalmykia, Bair Khodzhaev (“Mandjik’s Notes”). He and his team have made several full-scale comedic films based on his Instagram videos. This is an example of the popularization of the “Baldyr” Kalmyk spoken by young Kalmyks, with a large number of Russian borrowings and strange syntactic constructions. “Baldyr” is what Kalmyks call children from a mixed family, and “speaking Baldyr” is when a Kalmyk speaks badly, with a Russian accent. The idea is that Baldyr can also be spoken in a funny, fashionable and interesting way, and that people have the right to speak the way they speak. This is a very important message and I hope it will spread.

Kalmyk will survive if it is spoken by many people, preferably a younger age group. And, of course, when they start talking, they’re not speaking some high, archaic beautiful version of Kalmyk.

I think it’s important for these minority languages to come into fashion, that knowledge of the language is placed as high as possible on the hierarchy of prestige. Then, I presume, people will start thinking about the language — not just native speakers who inherited it in their childhoods, and not just language activists completing their latest project, but ordinary families who lack freedom of language. In Soviet times, minority languages were often associated with the village and the elderly. I haven’t seen this lately. On the contrary, it is prestigious to know your own language. People used to be ashamed to speak it, now it is shameful not to know it. I remember one Chukchi woman told me, “At first you forbade us from speaking ‘foreign’ and laughed that we did not know Russian or spoke with an accent, and now you say that we do not know our native language, we have lost our culture.” It’s shameful either way.

Yes, it’s terrible, actually.

A language has many layers, and there’s always the memory of its previous states, as well as the current context. And so people remember how the language was persecuted or how unfashionable it was.

In the 2000s, Kalmyk speakers in Kalmykia were teased and called “kolkhozniks” or “Gascons”. Each individual exists with all these levels of symbolism and tries to withstand them. I have also seen the growing prestige of minority languages in many communities — it’s commendable, fashionable, and good to speak your native language. At the same time, those who don’t speak the language, or do so poorly, are stigmatized.

But this is actually connected to the Russian linguistic ideology as a whole: it is monolingual and, as the American linguist James Milroy writes, focused on standardization. Russian should be very standard, unified, it should be spoken beautifully. And therefore Udmurt, Kalmyk, and Chuvash should be the same. That’s why it’s important when projects like “Manjik’s Notes” promote speaking a mixed language. Are there any projects in Russia related to language activism? Not just symbolic, but actually influential?

Symbolic ones also have influence, they make the first push. How wonderful it is to speak your own language! What do you gain from it? Or why don’t you speak your own language?

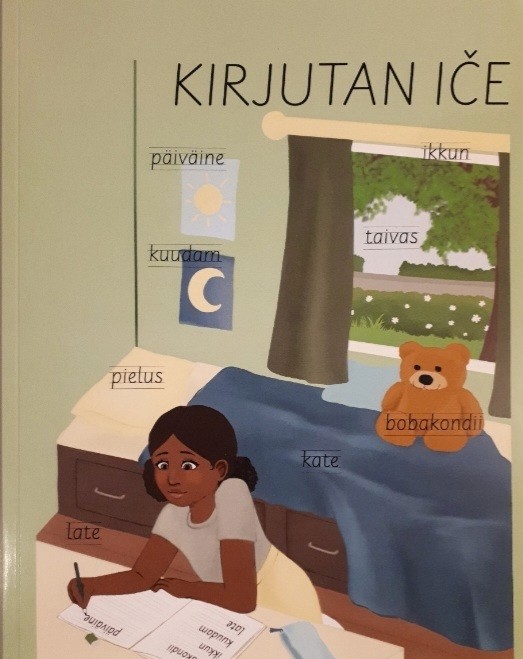

But, of course, people are often more focused on what has a lasting effect, and above all, this is working with children. The most effective tool for revitalizing a language — that is, to bring it back from the brink of extinction — is a language nest. This is where children are surrounded by adults who speak the minority language, in a kindergarten or other community setting. In Russia, there is only one successful language nest, in Karelia, which is being organized by Natalia Antonova from the Karelian Language House. It is very labor-intensive work, but it produces significant results.

Short-lived, but evocative projects are also very important. Preserving a language involves everything that makes a language popular, everything that makes a language accessible and part of the everyday lives of the younger generation. It’s not something that lies in your grandmother’s old trunk and only comes out at festivals, but something that is a part of the city culture, of youth culture, of online communication and various interesting collaborative projects. This is already well underway in Izhevsk or Kazan, for instance.

Everything that provides language-related opportunities is significant. For example, Vasily Kharitonov, a linguist and Nanai language teacher in a village in the Khabarovsk Krai, believes that it would be good to have some form of secondary education, like a technical school with important, interesting, and in-demand subjects in minority languages. Or there was a project in Yakutia with editing and vlogging courses only available in Yakut. Want to participate? Great, you can come. If you know Yakut well enough, you can learn how to edit videos — something that many teenagers want. Don’t know it? Well, sorry — learn Yakut and come back later. Intentionally learning a language can be quite boring, but when we learn it while cooking meat or shooting vlogs, it’s a completely different matter.

Why are minority languages such a painful subject? Why are they so politicized?

Language is always very politicized, it’s not just in Russia. The topic of having signs in the Basque language in Spain is also a very painful subject for the Basques. But, oddly enough, these are not the most important elements of preserving a language. Whether or not there are signs in a language is less important for its preservation than the language that the children are exposed to in kindergarten or at home. But the issues that are of the greatest symbolic significance are school instruction and signs, something that’s regulated by the state.

And does the language they speak with the children at home depend on the state?

It depends primarily on the community. But the state language policy certainly has an impact. What is important is the general context in which the ethnic group is located, how much they realized they were being persecuted, how much they understood that their language was not considered prestigious, how much direct political repression was carried out against this group — deportations, for example.

How can one characterize the state language policy in Russia after the collapse of the USSR?

It seems to me that it wasn’t the same story across all of Russia, and we didn’t start from a blank slate. There’s the memory of the deportations among the Kalmyks, or, on the contrary, the idea that the Karelian language will advance us and make us part of the Finno-Ugric world.

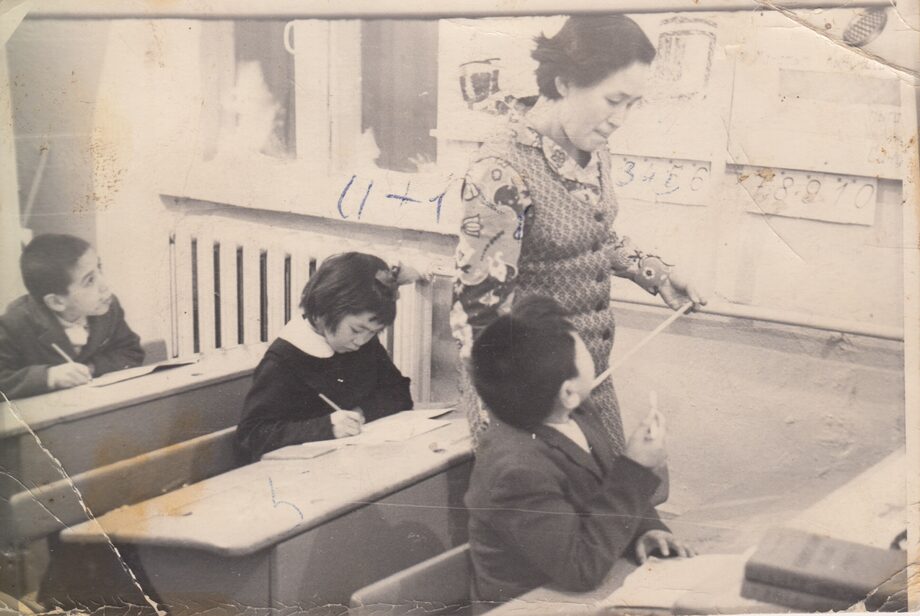

After the fall of the USSR, the same people continued to engage in language politics. They simply reprinted all the textbooks, and new ones only appeared in the early 2000s. It was a big problem. The old textbooks were written back in the 1960s and are aimed at children who had a good command of the language.

If we’re trying to highlight common features, then after collapse there was a feeling that you could now take symbolic political action aimed at promoting the language. But in reality, their work with the language was clearly not enough. Evidently they lacked the resources.

Then the centralization and restriction of linguistic rights began to creep in. It was against this backdrop that the demand for the use of minority languages rose in many regions. Some of the regional elites responded to this.

Let’s talk about the 2018 amendment, after which study of official native languages in the national republics of Russia has ceased to be mandatory, and has instead become voluntary, at the request of parents.

In 2017, Vladimir Putin delivered a speech saying that no one should be forced to learn a language. In 2018, the amendment was adopted. This caused a lot of anxiety, there was a lot of emotional pressure on parents when choosing the language of instruction, there were protests in the regions, which were quite severely suppressed, especially in Bashkortostan and Tatarstan. The sense of injustice associated with this law has greatly affected all speakers of minority languages. At the same time, it was clear that people outside the republics were doing a lot of wonderful things.

There has always been language activism, and in the last 10 – 15 years it has begun to grow noticeably.

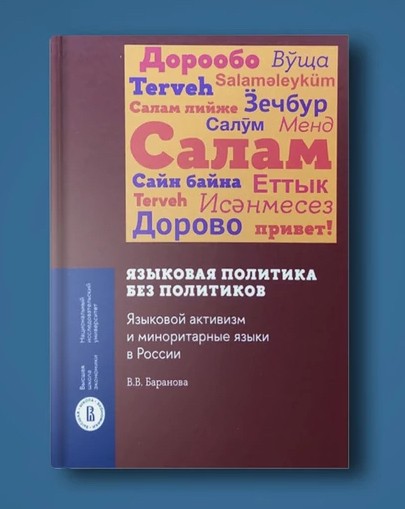

My second book, Language Policy without Politicians. Language Activism and Minority Languages in Russia, turned out to be a little about what could have been. I wanted to write about the fact that, regardless of the official language policy, a lot can be done from the bottom up, grassroots, and how much you can change, what you can respond to. But in the current setting, even this version of language policy is not very feasible.

How do you see this transformation?

In recent years, especially during the pandemic, a lot of fantastic online communities, forums and groups popped up: Strana iazykov (Land of languages), Za iazyki RF (For RF languages), and others. Before, language activists only knew about people in their own circles, those who were doing something to preserve Kalmyk or, for example, Buryat.

With the development of these communities, language activists began to exchange views, meet, organize collaborative projects. There was a wonderful series of video conferences titled “Best Practices for Preserving the Languages of the Peoples of Russia,” where they talked about children’s bilingualism in Yakut or Udmurt, discussed how to draw comics, how to set a background on your phone or use a voice assistant. Alas, these initiatives are crumbling, there are too many problems, and some of the language activists have left the country.

Researchers often distinguish two main dimensions of language activism. The first is protecting linguistic rights, a social movement in support of language (language advocacy), as defined by the linguist from the University of Oslo, Haley de Korn. This is when language activism becomes part of civic activism, the struggle for rights, for the inclusion of the language in the education system, for the opportunity to hold votes or some kind of events in the native language. Protecting linguistic rights is all about being included in the legislation and transformation at a large political level. And the second part is cultural initiatives. Russia’s language activists, perhaps because they existed in a repressive regime, focused on cultural and linguistic projects: they filmed cartoons, recorded rap, organized free courses.

Very few have engaged in language activism as a defense of linguistic rights — demanding that the law on education not be amended or that they comply with current legislation. There is a famous video in which a Komi activist demands that the judge speak Komi to him. But in general, this dimension has never been very well developed.

Now, language activists have felt that language activism is impossible without a struggle for rights and a coherent political agenda related to language and the rights of minority groups. And they radicalized, moved in the direction of protecting linguistic rights, which became completely incompatible with linguistic activism focused on collaboration with the state, on cooperation.

The word “collaboration” in Russian doesn’t sound very good now, but it didn’t necessarily have such a derogatory connotation before. Some language activists expect this kind of work and cooperation to continue. For example, at the beginning of June 2023, the Literary Megapolis was held on Red Square in Moscow — an event dedicated to different cultures and languages.

And the part that has become very radicalized believes that language activism is now impossible without revising linguistic rights, without a social movement, without a clear agenda of decolonization.

Mariam Arslanova and Karina Ozerova published an article in 2021 stating that in modern-day Russia, different ethnic communities do not have the opportunity to enter into the political conversation and therefore replace the political conversation with a cultural one. Hence the horizontal initiatives to preserve local languages. This is also political language, just veiled. Now the opportunity does exist, but only for those who left.

Yes, and those who remained, of course, do not have such an opportunity. Mariam Arslanova connects this with politics, fear, and anticipation of backlash. And it also shows that many initiatives have moved online, as it’s a safer space. But I'm not sure it's just fear. Many of the activists I interviewed really just wanted to do their language projects.

We have a very weak political culture in general, so people, whether they like it or not, move towards culture and avoid talking about politics.

Yes, and this is noticeable in many republics. Indiana University anthropologist Katherine Graber has a note about Buryat media in her book. From American experience, she expected that everyone would talk about the rights of indigenous peoples, but these words, this rhetoric, this discourse turned out to be inapplicable to the Russian context. People almost never used the term "indigenous.” It is actively used by those in the foreign category "indigenous peoples of the North,” Nivkhs or Udege for example, but those who have a republic almost never used these words.

Now we see how these ideas and the language itself are spreading among activists. The word “indigenous” is heard more and more often, they talk about decolonization, about the empire. I see this in the expatriate community of Kalmyks and Buryats in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Decolonization and discourse on the empire are still minority concepts held by young and more or less educated people. They do not find any understanding or support, I assume, among the majority. Or am I wrong?

Yes and no. It’s true, these issues have become the lot of a small number of people who have mostly left the region. People are looking for answers: What's going on? Why is it dangerous for them to stay in Kalmykia, Buryatia or Tuva? But the ideas they’re appealing to — the injustice of the leaching of resources from the regions to the center, the injustice of forcing different groups and members of different regions to participate in the war — these ideas easily find support.

We’ve been discussing language activism for a while, but what exactly is it?

It’s an interesting story, because not all language activists call themselves language activists. In essence, language activism is any activity that aims to support and restore a language that is in a vulnerable position, or increase the number of native speakers.

Is an elementary school teacher a language activist?

By default, no, but if this teacher uses their experience in teaching a language, makes a cartoon and puts it on the Internet so that people learn a minority language, then this is the work of a language activist.

But many are working to popularize the language, promote native-language instruction and integrate into the public school system. They broadcast on public channels, on the radio, they teach in public schools, and they are generally part of this state policy of multilingualism, however superficial it may be. Where is the activism here? Does activism always imply some kind of opposition, something informal or non-state-run?

Actually, no. The careers of language activists are fluid, and indeed they may at some point cooperate with the official language policy. But activism suggests that these are grassroots initiatives that the people first devise for themselves, and then seek support. At the same time, the degree of personal loyalty to the state can differ wildly, and a significant part of Russian language activists wanted—and some still want to cooperate with the state.

And I must say, that even in a normal political system, this is even necessary, because a language policy can’t be a slapshot effort. At the same time, if the language policy is developed entirely by the state, it is very immobile. Language activism is able to quickly respond to regional peculiarities and idiosyncrasies, to changing technologies, the spread of TikTok, whatever.

The main milestones of the state’s negative interference in regional language policy happened in 2017-2018 and 2020, when amendments to the Constitution were adopted regarding Russian as the official state language. The first was practical, the second was quite symbolic. So as it turns out, this was a methodical move on the part of the state?

Yes, the ideas of centralization and reduced autonomy aren’t new at all. Previous reforms did not directly concern the language. For example, the 2007 education reform led to a significant reduction in the so-called regional component. A lot of things related to local history and minority languages, literature, in addition to the existing subjects "native language and literature" and "native language,” were carried out within the boundaries of this 25% regional component. It was a very significant step.

Some researchers, such as Dilyara Suleimanova, an expert on migration, Islamic education, and cultural policy in Tatarstan, believe that the introduction of the Unified State Exam (USE) also affected the language situation. The format of the exam anticipated that more and more people would be inclined to write it in Russian [the USE and Basic State Exam (OGE) can be taken in a native language, but few standards have been developed. The OGE is usually taken in the 9th grade in Bashkortostan and Tatarstan. It is now impossible to take the Mathematics Unified State Exam, for example, in a native language. — Author’s note].

Do we consider the government of recent years to be an enemy to minority languages?

At this point, yes, to some extent. The language policy of recent years has not been unequivocal, including the ethnic language policy. On the one hand, it had repressive dimensions, such as changing the law on education, which abolished the compulsory teaching of minority languages and made it optional, by choice — a dubious choice that often has led and still leads to Russification.

Or some symbolic moments, like the changes to the Constitution and the idea of a “state-forming people and language,” which became a strong symbolic blow to minority languages. Against the backdrop of various restrictions in the ethnic republics, this meant that in a sense, the state was acting as the enemy.

On the other hand, programs to support both minority languages and interethnic diversity continued to operate in Russia. They are still in operation today.

Some language activists believe that even in the current political context, efforts should be made to ensure that the state supports the publication of textbooks in minority languages or gives money to make cartoons.

What kind of state policy do you envision that would be, on the contrary, positive?

What would be the ideal language policy? I think it would be very flexible and connected with the local level, with language activists — they really respond most quickly to a changing agenda, to requests from native speakers. They know best what the community needs. The overall umbrella part of the language policy could be spelled out, but only the most important things, such as the fact that all languages are equal.

The second point, which I think is very important: linguistic rights are individual-level rights, like any human rights. And we always talk about linguistic rights as group rights, and often in relation to territory. But in general, the language policy should be focused on the rights of the individual, so that these are not the prescribed rights of the indigenous group that lives in the villages, in groups, collectively, but rather the rights of each individual person in this group.